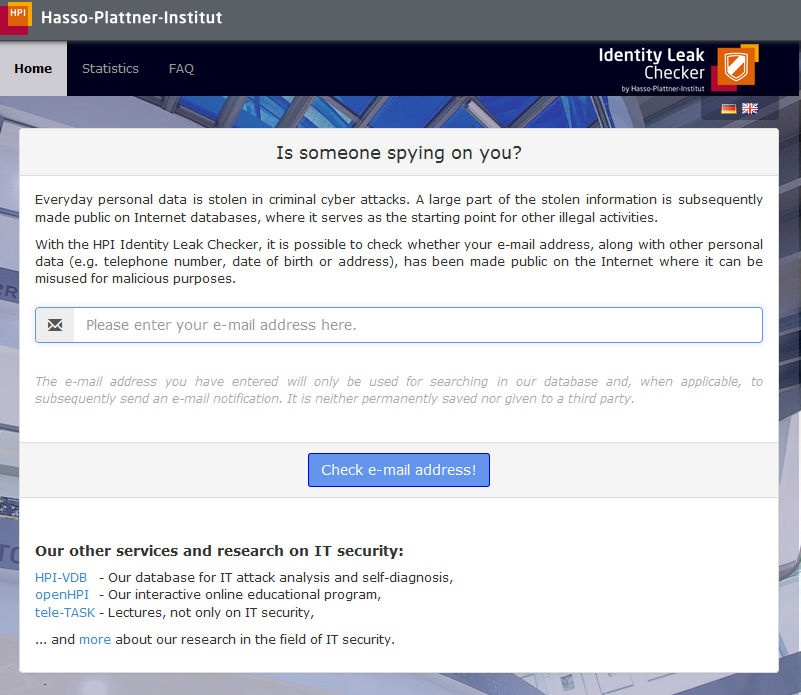

Have cybercriminals stolen my personal data and made them freely available online so that others might also access and misuse them? Internet users all over the world can now answer this question using a free service from the Hasso Plattner Institute for IT Systems Engineering at the University of Potsdam in Germany. All they need to do is visit https://sec.hpi.de and enter their e-mail address. The system will then search the Internet for freely available personal data linked to them.

If names, passwords, account details or other personal data associated with the e-mail address are found to be circulating the web, the HPI will warn the user via e-mail and give him/her tips about how to proceed. For security reasons, the institute will not disclose the precise nature of the data.

If names, passwords, account details or other personal data associated with the e-mail address are found to be circulating the web, the HPI will warn the user via e-mail and give him/her tips about how to proceed.

The computer scientists who developed the service have named their innovation the Identity Leak Checker. To date, researchers at the university institute, which is funded by SAP co-founder Hasso Plattner, have identified and analysed over 170 million sets of personal data on the internet. Some 667,000 free checks have been carried out since the service launched in Germany. In 80,000 of those cases, the users had to be informed that they had been the victims of identity theft.

“This type of warning system for stolen personal data circulating the internet aims to make users more aware of the way they handle their personal data,” says Prof. Christoph Meinel, director of the HPI. His department has also built a database for analysing IT vulnerabilities. It integrates and combines large quantities of data already available online about software vulnerabilities and other security issues. The database currently contains a good 61,000 pieces of information about weak spots that exist in nearly 160,000 software programs from over 13,000 manufacturers.

The HPI database has recently started helping users run free checks of their computers for identifiable weak spots that cybercriminals often skillfully exploit for their attacks. The system recognises the user’s browser – including commonly used plugins – and displays a list of known vulnerabilities. Plans to expand the self-diagnosis system to cover other software installed on a computer are currently in the pipeline.