By Raj Samani & François Paget, McAfee

The increasing frequency, variety, and complexity of attacks are the product of an emerging “cybercrime-as-a-service” provider market. This market allows malicious parties to execute attacks at considerably lower cost, with considerably lower levels of technical savvy.

As is the case with cloud computing, this service-based cybercrime ecosystem provides greater efficiency and flexibility to cybercriminals—just as it does in other “business” ventures. This approach extends well beyond hiring individuals to undertake specific tasks (such as coding an exploit) to include a broad variety of products and services available either to buy or rent.

This marketplace contains many stakeholders, ranging from formal, legitimate organizations selling vulnerabilities to parties that meet their strict eligibility criteria, to underground websites that allow individuals to offer illegal services. Law enforcement’s focus on cybercrime at a global level has led to “as a-service” models for illegal activities going even deeper underground.

Such underground platforms are implementing stronger mechanisms to ensure that participants are who they purport to be (or at the very least are not law enforcement officials). Ironically, while the platforms that facilitate the services marketplace for illegal activities are going deeper underground, the trade in zero-day vulnerabilities is more transparent than ever before.

Most of these services are clearly administrated by cybercriminals. There are, however, a number of services that remain legal. Overall, we can class services as part of black or gray markets. We use the classification “gray” when the activities or real customers are difficult to determine.

Research-as-a-Service

Unlike our other categories, research-as-a-service does not have to originate from illegal sources; there is room for a gray market. There are commercial companies that provide the sale of zero-day vulnerabilities to organizations that meet their eligibility criteria. And, there are individuals who act as middlemen, selling such intellectual property to willing buyers who may or may not have the same strict eligibility requirements.

Examples:

Vulnerabilities for sale: a commercial marketplace. Today’s marketplace serves those looking to acquire zero-day vulnerabilities—software vulnerabilities for which there is no known solution at the time of their discovery. This category is known for its customer eligibility requirements—such as requiring that customers are law enforcement officials or government organizations. Regardless of these requirements, these services can and are being used to acquire vulnerability intelligence for use in attacks.

Exploit brokers. Although the acquisition of vulnerabilities can be conducted via a commercial entity, there are opportunities to purchase through brokering services. This could be a single individual who acts as a commission-driven middleman to facilitate sales with third parties.

Spam services. Rather than manually building email lists, would-be spammers have the luxury of simply purchasing a list of email addresses. Aside from the customization of the message in a particular language, the unsolicited email may require more granularity. For example, if there is something particularly relevant to consumers in a US state, there are services that supply email addresses belonging to individuals from specific states.

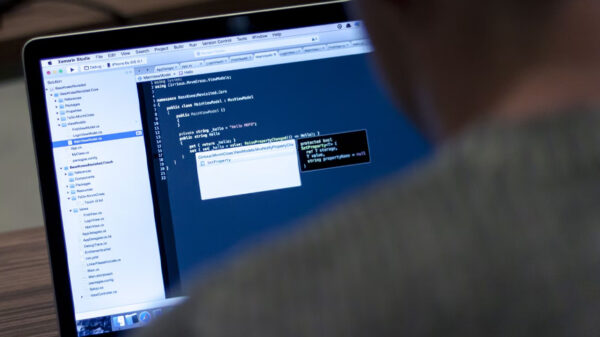

Crimeware-as-a-Service

This category incorporates the identification and development of exploits used for an intended operation—and may also include the development of ancillary material to support the attack (droppers, downloaders, keyloggers, bots, and more). It includes tools used to conceal malware from security protection mechanisms (cryptors, polymorphic builders, joiners, crackers, and the like), as well as spammer/robot tools like XRumer. In addition, this category includes the availability of hardware that may be used for financial fraud (for example, card skimming) or equipment used to hack into physical platforms.

Examples:

Professional services. The outsourcing of malicious code development has been around for some time, with some specific examples of malware being outsourced to a third party. An example of this was seen as early as 2005, when a programmer was hired to develop the Zotob worm, a strain of malware that required an estimated $97,000 to clean off of impacted systems.

Malware services. Purchasers can acquire predeveloped code to conduct their attacks:

• Trojans. A malicious program that is concealed within a legitimate file to steal user information or login credentials from an infected system

• Rootkit services. Surreptitious code that conceals itself within the compromised system and performs actions as programmed

• Ransomware services. Software that restricts the user from conducting further activity until a specific action, such as providing credit card details

Exploit services. Crimeware-as-a-service also includes exploit packs that offer capabilities such as encryption services for concealing an attack and avoiding detection. This may include encrypting particular files, which may be used in conjunction with other techniques using encryption to further disguise the malicious code. Other service providers test cybercriminals’ malware for them against antivirus software, and test spam against domain blacklists. The latter are used by companies and service providers to block email from domains that are known to send content, such as spam, in violation of their policies.

Cybercrime Infrastructure-as-a-Service

Once the toolset has been developed, cybercriminals face the challenge of delivering their exploits to their intended victims. An example is rental of a network of computers to carry out a denial-of-service (DoS) attack. DoS attacks (or distributed denial-of-service [DDos] attacks) send a huge volume of traffic to victims’ websites or services and prevent them from conducting normal business operations by overloading them. Other examples include the availability of platforms to host malicious content, such as “bulletproof” hosting.

Examples:

Botnets. A robot network, or botnet, is a network of infected computers under the remote control of an online cybercriminal. The botnet can be used for a number of services, such as sending spam, launching DoS attacks, and distributing malware. Multiple services are available to suit any budget.

Hosting services. A “bulletproof” hosting provider is a company that knowingly provides web or domain hosting (or other related services) to cybercriminals. Such providers tend to ignore complaints by turning a blind eye to the malevolent use of their services. Much like the commercial environment, a myriad of hosting services are available—the only constraint is the amount of money one is willing to pay and, in some cases, the ethics of the hosting provider.

Spam services. Would-be spammers can use services that support the sending of unsolicited mail. For instance, a criminal can send 30,000,000 emails for a month-long attack without any equipment at his disposal.

Hacking-as-a-Service

Acquiring the individual components of an attack remains one option; alternatively, there are services that allow for outsourcing the attack entirely. This path requires minimal technical expertise, although it is likely to cost more than acquiring individual components. This category also supports the availability of information used for identity theft, for example, requesting information such as bank credentials, credit card data, and login details to particular websites.

Examples:

Password-cracking services. These services make it easy for a buyer to retrieve an email password—with no technical expertise. All that is required is the email address and name of the target.

Denial of service. DoS services simply require attackers to provide the name of the site they wish to attack, decide how much they are willing to pay, and then initiate the service. For only $2 per hour, for instance, an attack can be launched against the systems of the buyer’s choosing.

Financial information. Many services offer credit card information, with considerable flexibility and varying price models based upon the information sold. While credit card information is valuable to would-be criminals, login credentials for online banking can command a higher price than credit card numbers.

Conclusion

We are not only witnessing an increase in the volume of cybercrime, but also individuals partaking in these misdeeds are far removed from the public perception of the computer hacker.

The growth in the “as-a-service” nature of cybercrime fuels this exponential growth, and this flexible business model allows cybercriminals to execute attacks at considerably less expense than ever before.

Like law enforcement partners around the world, EC3 European Cybercrime is relentless in the pursuit of criminal groups or networks that steal your money, your information, or your identity and that engage in the online abuse of children.

Raj Samani is an active member of the information security industry through his involvement with numerous initiatives to improve the awareness and application of security in business and society. He is currently serving as the vice president and chief technology officer for McAfee, EMEA, having previously worked as chief information security officer for a large public-sector organization in the United Kingdom.

François Paget is one of the founding members of the McAfee Avert group (now McAfee Labs). He has worked there since 1993. Today, Paget conducts a variety of forecast studies and performs technological monitoring for his company and some of their clients. He focuses particularly on the various aspects of organized cybercrime and the malicious use of the Internet for geopolitical purposes.